UGA-led projects for NSF-funded CB2 ‘on track’ for 2020

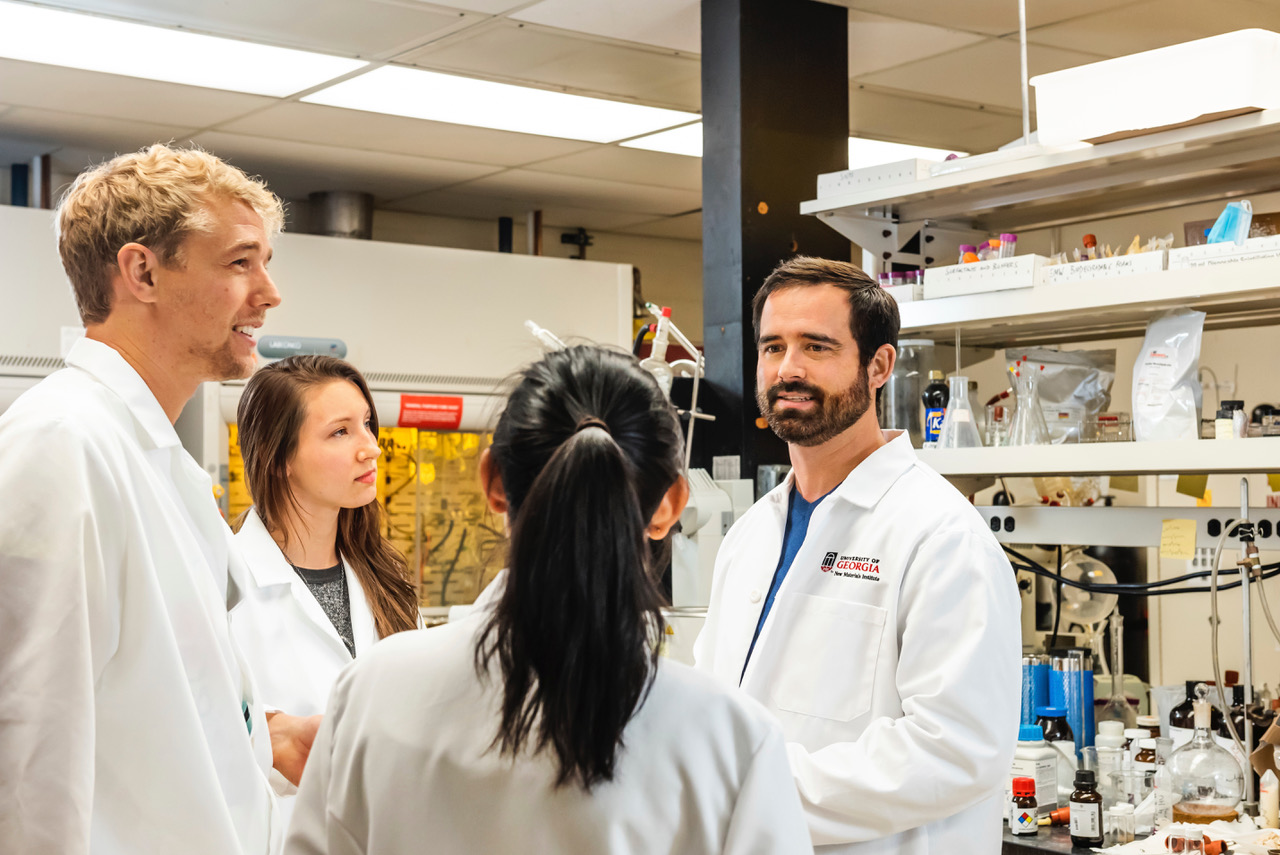

Two research projects that are being led by University of Georgia New Materials Institute received positive feedback at the spring meeting of the Industry Advisory Board for the Center for Bioplastics and Biocomposites (CB2), a National Science Foundation Industry—University Cooperative Research Center.

The projects, “Unlocking the Potential for Xylan-based Polymer Materials” and “Investigation of the Enzymatic Degradability of Glycolic Urethane Linkages Using Chromophore Probes,” are among nine that were selected by CB2’s IAB for research and funding in 2020. The other projects are being conducted at three other research sites, that, together with UGA, comprise CB2: North Dakota State University has three projects underway; Iowa State University and Washington State University each have two. Updates on all projects were presented by researchers at CB2’s spring meeting, held virtually in mid-May.

Pushing toward greater sustainability

“UGA is very happy with the feedback we got from the Industry Advisory Board, which indicates the member companies are satisfied with our work thus far and that we are on-track,” said Jason Locklin, director of the New Materials Institute and the UGA site director for CB2.

Project updates and pitches for new projects are the two main agenda items for CB2’s spring meetings. The pitched seed projects are then shaped to benefit the greatest number of CB2’s member companies, representing many different industries: Ford, Hyundai, 3M, Boehringer Ingelheim, Kimberly-Clark, Shaw, Sherwin Williams, as well as bioplastic resin manufacturers and packaging manufacturers. Through annual fees, they help share the cost of developing the technologies produced by CB2’s research teams, with the goal of adapting the technologies. Each member company is striving for greater sustainability in its product line.

“I am excited about the seed proposals pitched by the industry members for 2021,” said Locklin. “The ideas represent technologies that are desired by many companies involved in CB2, and the ideas present both a good fit and an intriguing challenge for the variety of research expertise we have among the four university sites. These projects also represent tremendous learning opportunities for our students.” Project selections for 2021 will be finalized when the board meets again this fall.

Insight from industry

The two projects being led by UGA are good examples of research that could take years to exit a laboratory if industry was not invested—financially and hands-on— and awaiting a timely outcome. Having industry involved helps the researchers better understand its needs, including recognizing what’s readily available and cost effective. The xylan project, for example, is focused on identifying plant properties which may be useful in creating bio-based polymers for materials and products. (The glycolic urethane project is focused on developing faster methods for screening enzymes that will deconstruct polyurethanes, which will aid in the development of completely compostable high-barrier, multilayer packaging.)

Breeanna Urbanowicz, who leads the xylan project, has investigated plant properties, with a focus on xylan, for years. In her spring update to the IAB, Urbanowicz noted that in consultations with her industry mentors to discuss test results, the mentors helped her see potential in another abundant polysaccharide from plants, because it’s commonly seen in their industrial waste streams. Based on this insight, her team is now exploring two naturally existing biopolymers that possess potential for replacing petroleum-based polymers currently used to manufacture single-use plastic packaging. Urbanowicz is an assistant professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, in the Franklin College of Arts & Sciences; she is based at the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center.

The xylan project, like all CB2 projects, is focused on non-food sourced materials for bioplastics. CB2 emphasizes use of agricultural byproducts, so that agricultural land is not utilized to grow crops for bioplastics and biocomposites.

Meeting held virtually due to COVID-19

The semi-annual meeting of researchers and CB2’s industry members was held virtually due to the COVID-19 outbreak. Faculty from CB2’s four research sites noted their work has been slowed by the virus, but forecasted their projects would quickly be on-track again once on-campus research ramps back up.

The UGA New Materials Institute’s participation as a research site for CB2 is supported by NSF Award #1841319.